Over the course of the next fortnight, stadiums across Europe will play host to the deceptively insignificant final round of qualifiers for Paris’ EURO 2016 tournament. The major surprise of the group stage – the capitulation of the Netherlands in Group A – has already been sprung. Elsewhere, the pre-qualification group favourites have performed as expected, with Germany, Spain, Italy and Portugal topping their groups, while a Belgium side that consistently flatters to deceive will play Andorra and Israel in the knowledge that a solitary point will secure seats on a one-hour flight to the French capital. England have already checked in their bags and booked the No.1 Lounge at Gatwick, and face Estonia and Lithuania with license to experiment. To take stock of their success up until this point, and prepare for the tougher tests that lie in store at the showpiece.

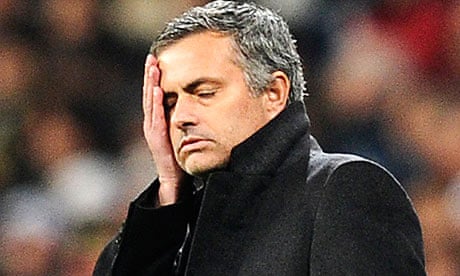

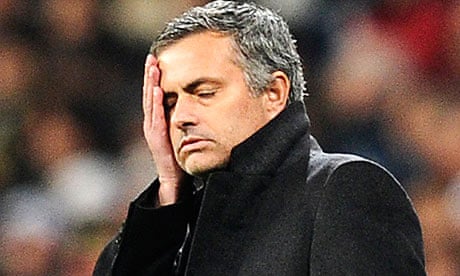

Before the start of the 2015/16 Barclays Premier League, Jose Mourinho imagined that he would be in the same scenario come October 4th. With the exception of a second matchday trip to the Etihad Stadium, Chelsea’s autumn fixture list looked to pose few problems. Stamford Bridge would play host to Swansea, Crystal Palace, Arsenal and Southampton, while little complication would have been anticipated with away days at West Brom, a struggling Newcastle and Goodison Park, in a game that yielded six goals for the Blues in 2014/15. The Portuguese may even have contemplated the tantalising prospect of replicating that season’s unbeaten start to the campaign.

This has been definitively shattered. Chelsea fans have been forced to suffer the taunts of previously unimaginable statistics from rival fans. Eight points from eight games. In eight of their opening eleven games in all competitions, the blues have conceded at least two goals. They have conceded seventeen goals in the league; last season, people were shaking off hangovers from New Year celebrations as Chelsea conceded their fifteenth (and then sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth) goal at White Hart Lane. Prior to this season, Mourinho’s Chelsea had only lost one league match at Stamford Bridge. They have lost two of their four games in front of the Matthew Harding stand thus far. Only one player has scored more than twice; none of Willian’s four goals have come from open play.

Chelsea’s catastrophic campaign has left fans, pundits and rivals utterly perplexed by the abysmal attempt to retain the Premier League title. So where did it all go wrong?

A SEASON OF TWO HALVES

Quite a lot earlier than has been documented, actually.

Much of the narrative surrounding Chelsea’s implosion has been framed like so;

“Chelsea were CHAMPIONS last season! They won the Premier League COMFORTABLY! This isn’t the Chelsea we know!”

And so on. Except the second statement isn’t actually true. Chelsea’s blistering start to the campaign is what clings to our hippocampus. This success did not begin when Andre Schurrle applied the perfect finishing touch to a mesmeric team goal, as beautiful as it was effective. It began in June, when Jose Mourinho and the executive board met to discuss the clubs transfer dealings. Fresh in the memory was the infamous victory at Anfield that ended Liverpool’s charge to the Premier League title. Chelsea had lined up with three holding midfielders in front of what would become a back five, and won 2-0, a score that would send Jose Mourinho chest-pumping his way up the touchline, courtesy of nothing more than a slip by Steven Gerrard. Mourinho’s aim was simple: survive, then capitalise. Many perceived that this was the only possible route to success, given the imperious form of Daniel Sturridge, Raheem Sterling and Luis Suarez, but more notably as a result of Chelsea’s own creative shortcomings. With Samuel Eto’o, Fernando Torres and Demba Ba ageing, injured and painfully average, the squad desperately lacked a currently prolific goalscorer, and a deep-lying playmaker to supply them, with Frank Lampard’s influence declining with age and Chelsea’s 4-2-3-1 formation.

Both boxes were ticked with staggering success and speed. £32m brought Diego Costa, whom pundits would soon unanimously declare the perfect Premier League centre-forward, to London following a remarkable season with Atletico Madrid. The Brazilian-cum-Spaniard’s strength, power and snarling attitude combined with clinical, nerveless finishing prowess are the embodiment of Mourinho’s values. This was augmented by the surprising yet sensational signing of Cesc Fabregas from Barcelona, a player with – ostensibly – two major reasons to never sign for a Chelsea side managed by ‘The Special One’. Fabregas was trained on the wrong side of the most high profile rivalry in London by Mourinho’s antithesis, Arsene Wenger, and then bore witness to the turbulent side of his management from the comfort of an all-conquering Barcelona side. The squad overhaul extended to the recall of arguably the world’s best young goalkeeper, Thibaut Courtois, the modest acquisition of the best left back in the world of that season, Filipe Luis, and Loic Remy, a prolific goalscorer with Premier League experience to provide more than capable competition for Costa.

Arguably more important than the players signed was the manner in which their acquisitions were completed. The sales of players then-deemed surplus to requirements at the Bridge, including Romelu Lukaku and David Luiz, ensured that Chelsea ended the transfer window in an unthinkable profit. Furthermore, Costa and Fabregas put pen to paper on lengthy contracts before Chelsea played their first match of pre-season; a relatively low-key affair, with matches against the likes of Fenerbache and Werder Bremen played both in the UK and within a short haul flight to the Continent. This reflected both the need to allow key members of the squad ample time to recover from their exertions in Brazil’s World Cup, but, more importantly, the need to integrate the new signings into the squad and a designated playing style. Put succinctly, style came before substance, in matches Chelsea could win without too much of the latter.

The combined result of a string of wins in pre-season, facilitated by an incredible transfer window, was a crushing wave of morale and optimism that carried Chelsea through to New Years Day. The confidence and technical understanding pulsated through Chelsea’s opening day victory against Burnley. Chelsea conceded an early goal, but each of the three scored in instantaneous reply epitomised both the ruthless efficiency of past Mourinho sides and the new threat the Blues posed; a beautiful team goal, a smashed close-range finish from Diego Costa, and a Fabregas set piece headed home by Branislav Ivanovic. Chelsea then played with reservation in the second half, secure in the knowledge that the game was won.

Until the first of the January, this was Chelsea’s campaign in microcosm. Fabregas continued to create goals for a fully fit Costa. Eden Hazard continued to exploit space created by the former’s range of passing and the latter’s reliability in front of goal. The steadying influence of Nemanja Matic gave licence to Fabregas to both dictate matches from deep and move forward with the offensive triumvirate behind Costa. This led to four goals against Swansea, six away at Everton, three at home to Tottenham. The list could go on. The confidence bursting through the team ensured that the first XI picked itself.

Then, Harry Kane came of age.

THE SECOND HALF

The current season has seen many managers claim the scalp of one of the most successful and iconic figures in modern sporting history. And they all owe one man their gratitude.

It’s not Harry Kane

.

.

Mauricio Pochettino had become renowned for the work ethic he demanded of his players before his arrival at Tottenham. Sources at Southampton recall being ordered to run on hot coals, and to “work like a dog”, to challenge both their physical and mental strength. Double training sessions quickly became routine upon his arrival, twice weekly throughout pre-season, and this eventually transformed Spurs into perennial choking cockerels into renowned scorers of late goals. Allied with an acute tactical understanding, this also relegated Chelsea from an unstoppable force into a very moveable object. On 1st January 2015, no player received more instruction than Christian Eriksen. The Dane is an inconsistent genius with the ball at his feet, but Pochettino ensured he won the match without getting near the scoresheet. For the first time, not only was Cesc Fabregas identified as a defensive weak link, but a way was devised to exploit it. Fabregas’ shortcomings without the ball are well known; he is by no means the quickest central midfielder in world football, and neither does he often show much inclination to use what little he does possess to track runners. Prior to the match, this did not matter. These failings were compensated for by Matic. However Pochettino second-guessed his Chelsea counterpart, knowing that Mourinho would identify Eriksen as the main supply line to Harry Kane, and therefore correctly assumed that Mourinho would instruct Matic to attach himself to the Dane. Pochettino then instructed Eriksen to continually make movements off the ball towards the channels. This would – and did – expose the unnerving lack of pace of Chelsea’s centre halves, and also widen the space between them, creating space for Kane & company to exploit when – and whenever – they received the ball in a central position.

The resulting humiliation sparked the chain of events that now see Chelsea in their current precarious predicament. Mourinho’s response was immediate and perhaps predictable. The creative freedom afforded to Fabregas was heavily restricted. The Spaniard signed for Mourinho as a player whom Chelsea would build the attacking elements of their play around. Now he was perceived as a defensive vulnerability the whole team should compensate for. Not only did Mourinho instruct Fabregas to reduce the number of risky passes he made and maintain a constant close distance between himself and Matic, Willian and Oscar were ordered to provide greater protection to Azpilicueta and Ivanovic, in the event that the full backs were targeted by a ‘third man runner’ to expose space in front of Terry and Cahill. This had the benefit of affording Eden Hazard – identified by Andre Schurrle of late as Mourinho’s ‘special one’ – carte blanche to attack. The effect of these changes was twofold. In combination with recurring hamstring injuries suffered by Costa, Chelsea became increasingly dependent on Hazard. Thankfully for Chelsea, the mercurial Belgian delivered. It was his form in the second half of the season that virtually guaranteed a clean sweep of individual awards. The second consequence was much more intentional. After the final whistle on the first of January, Chelsea had scored forty-four goals. From this moment until securing the title at home to Crystal Palace four months later, they only managed twenty-five. Five of these came against Swansea, one of only three games in this period that Chelsea won by more than one goal. But this alarming decline in output did not worry Mourinho. Chelsea’s defence conceded just eight goals in the same period. In Mourinho’s own words in conversation with Diego Maradona, ‘I score and I win’. Then, it did not matter that the signing of Juan Cuadrado utterly failed, forcing Chelsea to start Hazard, Willian and Oscar game in, game out. It did not matter that Didier Drogba scored once in seventeen appearances in 2015, leaving Loic Remy as Costa’s only stand-in. It did not matter that Chelsea possessed no ‘pivot’ midfielder that could be brought on to change a game. One goal was all it took for Chelsea to win matches. One spectacular moment from an enfranchised Eden Hazard per ninety minutes was all it took for Chelsea to win the Premier League. A consistent team selection, subjected to consistent dogma, had yielded consistent results.

But at what price?

THE HANGOVER

We highlighted that it is often said that Chelsea breezed to the title. We can clearly see that the manner was more akin to a funeral march. Chelsea were unanimously praised in publicised season reviews for their beautiful attacking play and ability to produce results. But never did the two coincide. From January, Mourinho’s ruthless pragmatism had deprived his squad of morale, creative freedom, depth and fitness. Chelsea’s breathtaking attacking play in the opening half the season had afforded Mourinho the privileged position of managing a team where the first eleven picked itself. Meanwhile, the remainder of Chelsea’s squad players either stagnated or agitated for a move away from Stamford Bridge. This meant that, after humiliation against Spurs, Mourinho had to – or believed it necessary to – orchestrate a complete change in playing style, using the same fourteen players that put Chelsea in its current position. The result would be plummeting morale in the squad. The chosen few would exhaust themselves in pursuit of the Premier League title, forgetting what it was like to enjoy playing football and scoring goals for their own sake, while isolation beckoned for the rest. John Terry went on to lift the Premier League trophy, so it must be argued that Mourinho’s changes were successful. But to say that Chelsea coasted to the title, winning it in comfort, is a complete falsehood.

PRE-PRE-SEASON

With the Premier League (and Capital One Cup) secured, the club’s focus began to shift towards pre-season. It should have been clear that pre-season should have been targeted at rediscovering the optimism and flair that had been lost over the course of a functional spring. Chelsea’s fixtures should have afforded the key players in the squad the opportunity to recover from their gruelling campaign, with sufficient days and short flights between matches, and rediscover the sensation of scoring goals and playing without fear, through playing mediocre opposition. Central to this would have been re-establishing Cesc Fabregas’ pivotal role in the teams identity. Chelsea’s playing style had transformed from one built around the strengths of Fabregas’ game into something that compensated for his weaknesses. This had to be reversed; Fabregas’ decisive creative contribution was the sole reason Chelsea had a foothold to cling to in spring. Removing the pressure from, and therefore granting greater freedom to, Chelsea’s key players would also require a transfer window akin to the previous summer; with squad depth of genuine first-team quality signed quickly, in order to allow effective integration into the squad and playing style prior to the competitiveness of the Premier League.

Chelsea never failed to miss an opportunity. The first major mistake was to schedule a post-season tour/victory parade/marketing event of two fixtures played in Australia and Thailand. Despite being omnipresent and recovering from injury respectively, Eden Hazard and Diego Costa, along with the majority of the first team squad, were commercially obligated to be involved in both matches. Jose Mourinho was obligated to rationalise the fixtures as a ‘good way to celebrate’ away from the ‘pressures and tensions of the Premier League’. With a squad comprised of exhausted key players that wanted to celebrate with their families, squad players that felt that they had played no part in Chelsea’s success, and reserve players that wanted no part in Chelsea’s future, it was no surprise that the victory parade produced two stale 1-0 victories.

DID SOMEONE SAY 2014?

After landing at London Heathrow in early June, the squad were finally allowed to break up for their well earned and belated holidays. However, it appears that the rest of Chelsea Football Club did too. It was not until one month later that Chelsea made their first signing of the transfer window. Radamel Falcao scored just four goals in twenty-eight matches while on loan from Monaco at Manchester United. The Colombian centre-forward arrived with the odds resolutely stacked against him, having experienced the excruciating physical pain of rupturing a cruciate ligament, the consequent psychological pain of missing a South American World Cup at the peak of his career, and a significant effect on his match fitness. Falcao was then expected to replicate his world-class pedigree in a team that changed formation and personnel game in, game out, as Louis van Gaal struggled to understand how his philosophy would manifest itself at United. Furthermore, Falcao’s lack of English language and uncertainty over the length of his stay in England meant that Falcao would never settle at United. Jose Mourinho’s “close” relationship with Jorge Mendes ensured that Falcao would get another chance in the Premier League, at a heavily discounted price to Chelsea. Chelsea’s reaction to the signing was mixed; between those that expected Falcao to set Old Trafford alight, and those that understood that the Colombian could only improve at Chelsea. He would not be signed as Chelsea’s first choice striker, his understanding of England and its football was strengthened, and the Chelsea dressing room was dominated by South Americans, Spanish speakers and former team-mates. Yet Falcao’s arrival made no difference to Chelsea’s starting XI, and by the same date the previous summer, Chelsea had already signed Costa and Fabregas. The contrast could not have been starker.

Chelsea’s next move was to replace Arsenal-bound club icon Petr Cech. The previous summer, Chelsea had signed a former Arsenal hero. Chelsea reciprocated. The transfer was received with empathy by both the club’s fans and owner. Over the past eleven years and countless trophies, Cech had earned the right to leave Chelsea and remain in London for the sake of his family, in pursuit of more game time that had been denied by the return of Thibaut Courtois. But the fans pessimism was shared by Mourinho. Both understood that no matter who was signed, Chelsea would be worse off for the deal. Mourinho refused to give the deal his blessing. But it happened anyway. Chelsea promptly signed Asmir Begovic for £8m from Stoke as an able deputy to Courtois. Privately, the first undercurrent of hostility between Mourinho and his executive was stirred. John Stones was then targeted, with a £20m bid flatly rejected by Everton. At this stage the incredibly promising one-time Barnsley centre-back was thought of as a long-term successor to John Terry, maybe one day as captain. For the time being, he would serve as competition. This was not to remain the case.

THE INTERNATIONAL COMPLACENT CHAMPIONS CUP

Having exhausted the first team squad on a post-season tour, and then failing to improve it in the transfer market, Chelsea embarked on a pre-season tour that ticked every conceivable wrong box. Chelsea would fly to the United States to participate in the International Challenge Cup, consisting of three matches – against New York Red Bulls, Barcelona and Paris Saint-Germain – in as many states over the course of just six days. Chelsea lost the opening match against the Red Bulls 4-2. Mourinho’s post match press conference, intended as a statement of defiance, only served to highlight the enormous oversights that would explain the botched preparation for the start of the new season:

“I am the manager of the best team of England, we have top players, there are no fragilities. We have done 11 sessions in six days. We trust these players. We play this team 10 times, we win nine – but the second half was a disaster. If we had won 10-0 that wouldn’t have been any good. We needed a test and we received one.”

The first conclusion we can draw from this statement is that Mourinho had been lulled in to a false sense of security. Some may call this semantics, but the claim that there were ‘no fragilities’ in his squad showed that the manager thought he had found a defensive solution for his team’s problems in the final third. Chelsea’s resolute stumble to the Premier League title had fostered a complacency about a diminishing offensive output. It did not matter that a forward line that at any given point contained Fabregas, Oscar, Hazard, Remy and Diego Costa only scored twice against a mediocre side playing their academy players. Chelsea would have scored enough goals to win the game, had it not been for a second half which saw academy products given run-outs. The ‘I score and I win’ doctrine would have been executed. No value was attributed to the confidence gained by scoring a hatful of goals. Mourinho overlooked the long-term benefits of rediscovering a clear identity when moving the ball forward. Much more important was a test for his trusted players. A test they were not prepared for as a result of ignorance or of the impact of such a concentrated period of training on an already exhausted squad, and the absence of new first-team quality signings. Following these points, it is clear that prior to crossing the Atlantic, Mourinho thought his team would be in a position to overcome the challenges faced by their pre-season opponents, and that doing so would be the best possible preparation for the upcoming campaign.

Two incorrect assumptions. Based upon a complacency that had no reason to have develop. Two 2-2 draws against second-string Barcelona and Paris Saint-Germain, combined with a home defeat in the ‘Cuadrado’ friendly against Fiorentina should have proved that Chelsea did not have the style to bring home the substance Mourinho craved, and worsened the lactic acid building up in the legs of the first team squad.

COMMUNITY? SHIELD?

Chelsea’s last action of a rotten pre-season was to contest the Community Shield against Arsenal. A fixture that Chelsea were able to participate in because they had won the league. A fact that was relished by Mourinho, and paraded in front of Arsenal’s ‘specialist in failure’, Arsene Wenger. Their personal rivalry pressured Mourinho in to making yet another sacrifice in the name of substance over style. Chelsea’s team sheet read as follows;

Courtois; Ivanovic, Cahill, Terry, Azpilicueta; Fabregas, Matic; Willian, Hazard, Ramires; Remy.

The only two changes Mourinho made to his title-winning, exhausted side were enforced. One by Diego Costa’s continued absence through injury. Falcao was signed as a third-choice striker, it seemed. One was forced by Mourinho’s reluctance to risk losing to Wenger. Ramires was awkwardly placed on the right hand side of midfield, in order to attempt to shackle Arsenal’s threat from wide on the left – the normal starting berth of Alexis Sanchez, sensibly rested by Wenger after his heroics at the Copa America with Chile. Once more, Oscar, and with him Chelsea’s creative freedom, was consigned to the bench, marginalised in the pursuit of victory. The final score was 1-0 to Arsenal. Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain scored the winner early in the first half. Cesc Fabregas lost the ball upfield and did not track Theo Walcott, who found himself isolating Matic and Chelsea’s centre halves. John Terry, apprehensive of Walcott’s pace and wanting to support Matic, charged towards the ball. Walcott simply spread the ball to Oxlade-Chamberlain, who cut inside Azpilicueta into vacant space to rifle home. Chelsea did not force a save from Cech until a stinging free-kick from Oscar, late in the second half.

A North London side perfectly exploited a lack of defensive diligence from Fabregas, and a lack of pace in Chelsea’s defence. A familiar narrative.

Losing to Arsene Wenger for the first time in fourteen attempts seemed to trigger an epiphany in Jose Mourinho. The tension between the Portuguese and the club’s executives began to simmer. In a thinly veiled swipe at Chelsea’s lack of transfer activity – initiated by his own complacency – Mourinho claimed that Max Gradel, Georginio Wijnaldum and Yohan Cabaye, new signings for Bournemouth, Newcastle and Crystal Palace respectively, could all play for Chelsea. The club’s pursuit of Stones intensified into aggression and hostility between Mourinho and Roberto Martinez and a series of escalating bids, into astronomical sums that made it clear that Stones was more of a short-term necessity than had been previously thought. The bids publicly undermined the defence that had won Chelsea the league title, a sense exacerbated by Mourinho’s decision to substitute his captain for Kurt Zouma in the second half. It also made it fundamentally clear, for the umpteenth time, where Mourinho’s priorities lay.

I score and I win.

Therefore, prior to the opening match of the season against Swansea, the situation is as follows.

a) The first team, shallow as a result of last season’s lack of rotation and this summer’s lack of transfer activity, is exhausted from a challenging pre-season played across the globe.

b) The first team has not been in a physical condition to win its difficult matches, but this has been the focus anyway.

c) Chelsea do not have the confidence to play the expansive football, built around Fabregas, that gave its defence the foothold to cling to from January onwards.

d) The defence has been publicly undermined by Mourinho’s complacent, mistaken and retracted belief in its security.

e) Mourinho’s oversights in the transfer market have developed into a major source of contention between himself and the club.

KICK OFF

In this context – and with the ever-helpful benefit of hindsight – the events of Chelsea’s opening game of the season play out as little surprise. Chelsea take an early lead from an Oscar free-kick. From a position wide on the left, he swings the ball perfectly into an area of on-rushing players that paralyses Fabianski. He cannot stand still, in case someone beats him to it and heads in to an unguarded net. He cannot come for the ball, in case no one touches it. The ball nestles in the bottom corner for Chelsea’s first goal of the season. A goal of exquisite technical ability from Chelsea’s number 8. Instead of wildly celebrating, he just stands unmoved, then turns to glare at the bench. If eyes could speak a thousand words, they would only need two sentences here. ‘This is what I can do. Let me off the leash.‘ Mourinho returns the icy stare.

Swansea equalize swiftly. Jefferson Montero, a bundle of pace and trickery, with Matic in close attention dribbles comfortably past Ivanovic, who allows him to cross for Bafetimbi Gomis, who then forces an unbelievable save from Thibaut Courtois. Despite the close attentions of Terry and Cahill, the rebound falls to Andre Ayew, who fires a first-time rebound straight at the former. The Ghanian has time to simultaneously pick himself up and drag the ball away from the despairing defenders, a quite brilliant piece of skill, before lashing home into the bottom corner. Three shots on goal, in total.

In the background, you can see Cesc Fabregas, no more than ten feet behind Ayew. Walking.

Chelsea then restore their lead, courtesy of a Willian cross that takes a freak deflection off Federico Fernandez and, seemingly impossibly, loops over Fabianksi through a narrow trajectory. Chelsea lead at half time, through a set piece and an enormous amount of luck. Chelsea’s lead does not last. A simple ball over John Terry makes the captain look sluggish as Gomis bears down on goal. Courtois reacts late, clatters the advancing Frenchman, concedes a penalty, and is sent off. Gomis converts past the deputising Begovic – who replaces Oscar – to equalise once more.

A South Wales side perfectly exploit a lack of defensive diligence from Fabregas and a lack of pace of Chelsea’s defence. A familiar narrative.

Predictably, Eden Hazard, the depleted team’s sole creative outlet, creates a host of chances that Chelsea fail to convert. He is then involved in a nasty challenge, and writhes in apparent agony on the pitch.

No one could have expected what happens next.

CARNAGE OF EVA CARNEIRO

Eva Carneiro and Jon Fearn run on to the pitch, performing their duty as doctors to attempt to treat someone they reasonably believe to be injured. Jose Mourinho promptly begins to scream at his medics, realising that as they have entered the field of play, Eden Hazard will have to leave the pitch, leaving Chelsea down to nine men and increasing the risk of conceding a third, and possibly winning, goal. Fortunately, from a Chelsea perspective, Mourinho’s fears are not realised, and his team survive scare-free until Hazard resumes play. This does not stop a heated exchange in Portuguese between manager and medic as Carneiro returns to the bench. This should have been the end of the matter.

Instead, Jose Mourinho, anxious to talk about something over than a calamitous defensive performance that saw his team twice forfeit a lead and concede the most amount of shots on goal from an away team at Stamford Bridge in its history, vented about the ‘naivety and impulsiveness’ of his club doctors making sure his star player was unhurt and able to carry on unlocking the Swansea defence. Carneiro would never work for Chelsea again, instigating a number of investigations against her former boss – with allegations of unfair dismissal and sexism – on her way to the back door exit.

The media frenzy surrounding the scandal was arguably the fiercest Mourinho has ever encountered. But this was not the significant aspect of the crisis; Mourinho could channel the media attention to create a siege mentality, if his players bought into it.

If.

For the Eva Carneiro scandal has quickly turned an already tense relationship with his exhausted, marginalised and undermined players into a toxic one. This extends beyond the fact that Carneiro had been with Chelsea for six years, and was an immensely popular figure amongst players. Chelsea were able to win the Premier League in 2014/2015 with such a depleted squad for two fundamental reasons; firstly, because the work of the medical staff was fundamental in maintaining player fitness below breaking point; and secondly, because Eden Hazard would take risks. As discussed, post-January the team structure was conducted so as to allow Hazard to operate without defensive responsibility and with the licence to take on – and always beat – defenders. Whenever pressed on the subject in interviews, Hazard informs us that he rates his performance in terms of the number of times he is fouled. The more times he is fouled, the more the opposition team have found themselves unable to cope with him. Now put yourself in Hazard’s shoes. A popular figure in your team, and arguably the reason you achieved the biggest success of your career, is sacked because you stay down after a tackle. After taking a risk. How do you respond?

You feel guilty. You take less risks.

It is no coincidence that Chelsea’s alarming increase in goals conceded has coincided with Hazard’s crisis of confidence. Chelsea’s wingers, creative midfielders, full-backs and strikers are all under strict instruction to protect the soft underbelly of central defence. They are exhausted and low on confidence, and cannot hope to fill the void left by Hazard’s slump. But that means that they have no choice but to try. To do so means abdicating some of their defensive responsibilities. Creativity cannot hope to succeed in the vices of a crisis of confidence. Failure here means being rendered vulnerable to the counter-attack. And pace is not something Chelsea’s defence is capable of responding to.

YOU TAKE THE BLUE PILL, YOU SEE HOW DEEP THE RABBIT HOLE GOES

The last match that Jose Mourinho would have wanted in this situation was Manchester City away. Yet exactly this lay in store. And the same themes inherent in Chelsea’s attitude to pre-season and the defensive frailties exposed by Swansea reared their ugly head, in very predictable fashion. David Silva found pockets of space behind Matic and in front of Terry and Cahill, who then could not handle the pace and sublime finishing of Sergio Aguero. Once more, the defence was publicly undermined as Terry was hauled off at half time, replaced by Kurt Zouma, as Mourinho claimed Chelsea needed a faster centre half to cope with Aguero. This revealed both an inexplicable oversight from Mourinho, in that Zouma should have started the game if this was the case, and his negative ideology. Chelsea were trailing by a single goal at the Etihad. While they had created few chances, they were still very much in the game.

Mourinho’s first thought? Damage limitation. For all of Mourinho’s claims to the contrary, this was not an effective policy. Chelsea were perhaps unlucky to see a legitimate Ramires goal chalked off for offside, and Eden Hazard forced a brilliant save from Joe Hart. But to say that Chelsea had ‘no problem’ in the second half, despite conceding a further two goals to add to Aguero’s opener, and that the result was ‘fake’ as a consequence was a blatant lie. Only a catalogue of fine saves from Asmir Begovic, luck, and inept City finishing denied City a cricket score. Ivanovic was comfortably beaten in the air by Kompany for the second goal, and then – between himself and Fabregas – contrived to present the ball to David Silva on the edge of his own penalty area, with his colleagues in disarray as they began to mount a counter-attack. One pass to Fernandinho later, and it was three. Mourinho’s post match comments once more underlined his view that only the result of a match could possibly be conceived as significant. Chelsea’s shaky defence disagreed. Some cause for optimism was found post-match, with the signing of Baba Rahman, the young left back from Augsburg, confirmed for a fee of around £17m in the immediate aftermath of the game. The Ghanaian may not have brought the pedigree of Felipe Luis to the Chelsea bench, but he did bring pace and potential, and competition for Branislav Ivanovic. Or so it was thought. Rahman has played just one match for Chelsea thus far – a routine win over Maccabi Tel Aviv, in order to rest Ivanovic for his duel with Alexis Sanchez the following weekend.

Jose Mourinho’s failed campaign to achieve substance over style could not have been more perfectly illustrated by matchday three: an away trip to West Brom. Their last visit came in the form of a 3-0 defeat the game after Chelsea secured the Premier League title. The fixture was meaningless for both sides, and therefore there was no pressure on Chelsea to perform. There was now. The squad had received an enormous lift with the signing of Pedro from Barcelona, under the noses of Manchester United. Pedro had amassed a quite enormous collection of trophies over the course of a career at the Nou Camp. A serial winner that would take no time at all to settle in to a problem position for Chelsea, who decided to join Chelsea after a number of calls from Mourinho stressing his importance in his plans. The deal ticked all the boxes for an exciting marquee signing. Pedro made the debut to match his billing, with a sparkling first half yielding a goal after excellent link-up play with Hazard, and an assist for Diego Costa. But since that match – and because of what happened during it – things have proved to be too good to be true. Pedro made his debut at the Hawthorns just three days after signing for Chelsea, and took up position on the right side of a 4-2-3-1, in front of Ivanovic. For the entirety of Barcelona’s golden years, he had operated in a 4-3-3 formation, with the rapid Dani Alves behind him. The extra man in midfield and the independence of Alves ensured that Pedro was rarely asked to track back. Plus, against most teams during Pedro’s time at Barcelona, they could always score more goals. Pedro did not understand how to effectively support Ivanovic, and as a result, the Serbian was torn to shreds by Callum McManaman and James Morrison. Average wingers, at best, but enough to give Ivanovic a torrid afternoon. Combine that with Cesc Fabregas switching off defensively, and you get… a familiar narrative. Pedro has looked a shadow of the player since, with a fraction of the freedom. Chelsea won, by the skin of their teeth. 3-2, with West Brom missing an early penalty, and had John Terry sent off for a last-man tug on Solomon Rondon. The sending off of Terry meant that after the end of the home defeat to Crystal Palace, Chelsea had gone the first four games without naming the same back five in consecutive matches, or ending a single game with the same back five that started it.

Therefore, up until this point, Jose Mourinho had been putting out an exhausted first team squad that he was complacent enough to believe didn’t need strengthening until it was too late. With the creativity and freedom coached out of it, even that of the player that the change was designed to benefit. Which had been compensated for by a stable and holistic approach to defending, that has now evaporated as a result of injury, suspension, age, public humiliation and a lack of protection. Links between manager and squad have been shattered by restriction of freedom, overworking, and sacking of popular figures responsible for Chelsea’s title victory. In this context, it is not difficult to understand further defeats at home to Crystal Palace and Southampton, a 3-1 defeat at Goodison Park, capitulation against Porto in the Champions League, and a pitiful draw against Newcastle.

To describe the situation as a catastrophe does not do it justice.

SO WHAT CAN CHELSEA DO?

Roman Ambramovich and numerous members of the first team squad have come out in public to support Jose Mourinho. Those that have not, including Oscar and Eden Hazard, tell us far more about the reality of life at Chelsea than Jose’s devotees. I find it unthinkable to be saying this, but the situation is such that the best option for all parties would be for Chelsea and Jose Mourinho to part ways, amicably or otherwise. But that is simply not going to happen, especially with a rumoured £30m worth of compensation payable if it did. So we must now place ourselves into Jose’s shoes. Branislav Ivanovic has been a constant source of concern, against both quick and painfully average opposition. The right hand side of Chelsea is persistently targeted, and this is because Ivanovic, in such terrible form in the midst of uncertainty surrounding his future, is being isolated by the defensive shortcomings of an immobile Fabregas and an unaccustomed Pedro. Yet Mourinho has recently made it absolutely clear that he cannot drop Ivanovic, as Chelsea would become impotent at both defending and attacking set pieces, should he be replaced by the more slightly-built Rahman. This argument is fundamentally flawed, because Ivanovic has not offered a threat at offensive set pieces, and has been at fault for the few goals Chelsea have conceded from them. But there is a way to circumvent Mourinho’s reluctance to drop Ivanovic, with a number of additional bonuses.

The answer is to be found in the 4-3-3 formation.

As we have discussed, the vast majority of goals conceded by Chelsea have come about through insufficient protection for Chelsea’s full backs, widening the space between centre-backs in the process. Pedro could be removed from the spotlight and afforded the opportunity to meaningfully integrate into Chelsea’s squad, and replaced with a defensive midfielder. With Matic and Fabregas in the pivot, Matic is often isolated by Fabregas’ lack of positional discipline. With another defensively minded midfielder incorporated into Chelsea’s side, more freedom could be afforded to Fabregas, as Chelsea would always have a double-block on supply lines into dangerous positions, and the ability to cover a wider space. This could perhaps be seen as a more attacking variation of Mourinho’s infamous ‘trivote’ of Lassana Diarra, Sami Khedira and Xabi Alonso. But it would enable Fabregas to see more of the ball and have more options around him when he receives it, rebuilding both his role in the team and his confidence.

With Ivanovic’s attacking output faltering as quickly as his defensive contribution, Baba Rahman would naturally come in to the first team, with his occasionally ‘rash’ positioning compensated for by the third man in midfield. The Ghanaian showed enormously encouraging signs of an understanding with Eden Hazard against Maccabi Tel Aviv. As Rahman grew into the game, so did Hazard, who benefited from Rahman’s overlapping runs. Yet to drop Ivanovic would leave Mourinho one tall player short on set pieces. It is a happy coincidence, therefore, that Chelsea happen to possess a physically imposing defensive midfielder, comfortable enough in possession to demand the ball from established first team players, expanding the depth of Mourinho’s squad in the process – by allowing a potential bench of Begovic, Ivanovic, Ramires, Willian, Oscar, Remy, Falcao.

His name is Ruben Loftus-Cheek.

.

.